As I’m sure you learned in your high school civics course, the United States Government is traditionally thought of as including three branches. As you may also know, there is an additional aspect of the U.S. Government that is often called the “fourth branch” of government. The first three branches stem from the Constitution of the United States directly while the fourth branch receives its powers majorly from either statutes or the constitution.

These branches are: (1) legislative; (2) executive; (3) judicial; (4) administrative.

These branches are: (1) legislative; (2) executive; (3) judicial; (4) administrative.

Legislative Branch

All legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives. U.S. Const., Art. I, sec. 1.

These powers vested in Congress include:

The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States; but all duties, imposts and excises shall be uniform throughout the United States;

To borrow money on the credit of the United States;

To regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes;

To establish a uniform rule of naturalization, and uniform laws on the subject of bankruptcies throughout the United States;

To coin money, regulate the value thereof, and of foreign coin, and fix the standard of weights and measures;

To provide for the punishment of counterfeiting the securities and current coin of the United States;

To establish post offices and post roads;

To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries;

To constitute tribunals inferior to the Supreme Court;

To define and punish piracies and felonies committed on the high seas, and offenses against the law of nations;

To declare war, grant letters of marque and reprisal, and make rules concerning captures on land and water;

To raise and support armies, but no appropriation of money to that use shall be for a longer term than two years;

To provide and maintain a navy;

To make rules for the government and regulation of the land and naval forces;

To provide for calling forth the militia to execute the laws of the union, suppress insurrections and repel invasions;

To provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining, the militia, and for governing such part of them as may be employed in the service of the United States, reserving to the states respectively, the appointment of the officers, and the authority of training the militia according to the discipline prescribed by Congress;

To exercise exclusive legislation in all cases whatsoever, over such District (not exceeding ten miles square) as may, by cession of particular states, and the acceptance of Congress, become the seat of the government of the United States, and to exercise like authority over all places purchased by the consent of the legislature of the state in which the same shall be, for the erection of forts, magazines, arsenals, dockyards, and other needful buildings;–And

To make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers, and all other powers vested by this Constitution in the government of the United States, or in any department or officer thereof.

Executive Branch

The executive power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America. U.S. Const., Art. II, sec. 1.

As the executive, the President has the following powers and responsibilities:

The President shall be commander in chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the militia of the several states, when called into the actual service of the United States; he may require the opinion, in writing, of the principal officer in each of the executive departments, upon any subject relating to the duties of their respective offices, and he shall have power to grant reprieves and pardons for offenses against the United States, except in cases of impeachment.

He shall have power, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, to make treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur; and he shall nominate, and by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, shall appoint ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, judges of the Supreme Court, and all other officers of the United States, whose appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by law: but the Congress may by law vest the appointment of such inferior officers, as they think proper, in the President alone, in the courts of law, or in the heads of departments.

The President shall have power to fill up all vacancies that may happen during the recess of the Senate, by granting commissions which shall expire at the end of their next session. U.S. Const., Art. II, sec. 2.

The President and the Executive Branch interact with the Legislative Branch thus:

He shall from time to time give to the Congress information of the state of the union, and recommend to their consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient; he may, on extraordinary occasions, convene both Houses, or either of them, and in case of disagreement between them, with respect to the time of adjournment, he may adjourn them to such time as he shall think proper; he shall receive ambassadors and other public ministers; he shall take care that the laws be faithfully executed, and shall commission all the officers of the United States. U.S. Const., Art. II, sec. 3.

Judicial Branch

The judicial power of the United States, shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. The judges, both of the supreme and inferior courts, shall hold their offices during good behaviour, and shall, at stated times, receive for their services, a compensation, which shall not be diminished during their continuance in office. U.S. Const., Art. III, sec. 1.

The powers vested in the Judicial Branch include:

The judicial power shall extend to all cases, in law and equity, arising under this Constitution, the laws of the United States, and treaties made, or which shall be made, under their authority;–to all cases affecting ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls;–to all cases of admiralty and maritime jurisdiction;–to controversies to which the United States shall be a party;–to controversies between two or more states;–between a state and citizens of another state;–between citizens of different states;–between citizens of the same state claiming lands under grants of different states, and between a state, or the citizens thereof, and foreign states, citizens or subjects.

In all cases affecting ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, and those in which a state shall be party, the Supreme Court shall have original jurisdiction. In all the other cases before mentioned, the Supreme Court shall have appellate jurisdiction, both as to law and fact, with such exceptions, and under such regulations as the Congress shall make.

The trial of all crimes, except in cases of impeachment, shall be by jury; and such trial shall be held in the state where the said crimes shall have been committed; but when not committed within any state, the trial shall be at such place or places as the Congress may by law have directed. U.S. Const., Art. III, sec. 2.

The Judicial Branch interprets and applies the statutes promulgated by the Legislative Branch.

Administrative Branch

Administrative Branch

The Administrative Branch receives its power from the Legislature and the Constitution. Article I, sec. 8 of the United States Constitution states, in part, that Congress has the power

To make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers, and all other powers vested by this Constitution in the government of the United States, or in any department or officer thereof.

This section gives Congress the authority to vest or delegate determining authority in/to administrative agencies. There are dozens of different agencies, and the binding aspect of their authority varies based on the type of regulation and whether they’ve been delegated that authority by Congress. (Stay tuned for a post focusing entirely on the Chevron deference process.)

And just how do these branches interact? The American system employs a series of checks and balances amongst the different branches. These serve to limit the reach of each branch’s power.

And just how do these branches interact? The American system employs a series of checks and balances amongst the different branches. These serve to limit the reach of each branch’s power.

Essentially, the U.S. Government works together through different aspects of the legal system to create a government system that incorporates the different branches and their powers, as vested by the Constitution, into a system where, ideally, each branch works smoothly with the other branches.

The three main branches of government are the Legislative, Executive, and Judicial. The Administrative branch came about when Congress created agencies and delegated some rulemaking authority to them. Together, these four branches make up the United States Government.

The

The  “Procedural due process inquires into the way government acts and the enforcement mechanisms it uses. When government deprives a person of an already acquired life, liberty or property interest, the Due Process Clauses of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments require procedural fairness.” Constitutional Law in a Nutshell, pg. 274. Essentially, the government must use a procedural framework that “promotes fairness and transparency.” Acing Constitutional Law, pg. 125. Rather than using a narrow definition of these terms, the Supreme Court has interpreted “life, liberty, or property” quite broadly.

“Procedural due process inquires into the way government acts and the enforcement mechanisms it uses. When government deprives a person of an already acquired life, liberty or property interest, the Due Process Clauses of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments require procedural fairness.” Constitutional Law in a Nutshell, pg. 274. Essentially, the government must use a procedural framework that “promotes fairness and transparency.” Acing Constitutional Law, pg. 125. Rather than using a narrow definition of these terms, the Supreme Court has interpreted “life, liberty, or property” quite broadly. This does not mean, however, that you cannot advocate on your client’s behalf to introduce parol evidence to the court. You can, and should do so if applicable, so long as you can argue that the parties did NOT intend the contract at issue to be the final written agreement. Of course, you may be able to pursue alternative means of retribution for your client if the court rules that the contract is, in fact, intended to be the final written agreement between the parties.

This does not mean, however, that you cannot advocate on your client’s behalf to introduce parol evidence to the court. You can, and should do so if applicable, so long as you can argue that the parties did NOT intend the contract at issue to be the final written agreement. Of course, you may be able to pursue alternative means of retribution for your client if the court rules that the contract is, in fact, intended to be the final written agreement between the parties.

Students then learned about the three major learning styles: auditory; visual; kinesthetic. The presentation discussed the differences between them, including a

Students then learned about the three major learning styles: auditory; visual; kinesthetic. The presentation discussed the differences between them, including a

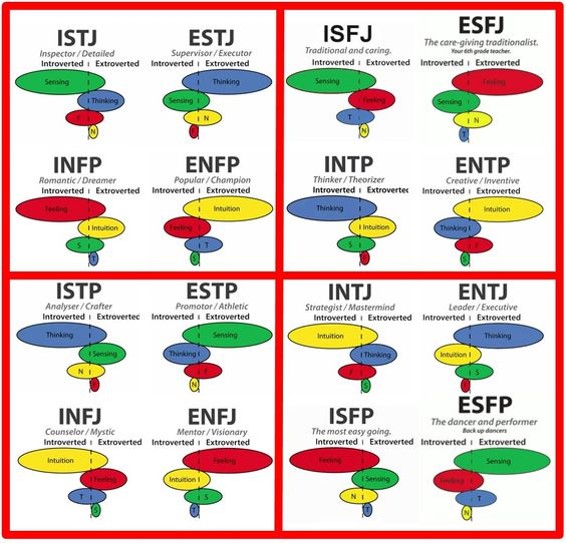

Dr. Brosseit also looked into how the MBTI types are distributed amongst lawyers. Of note, the top six types found in lawyers are:

Dr. Brosseit also looked into how the MBTI types are distributed amongst lawyers. Of note, the top six types found in lawyers are: Access to the law is vital to the practice of law. Within the United States of America, we have numerous expansive databases with the law, some free and some with a cost. But how do we access international law? The thought of subscribing to dozens of individual country sites can be overwhelming. That’s where

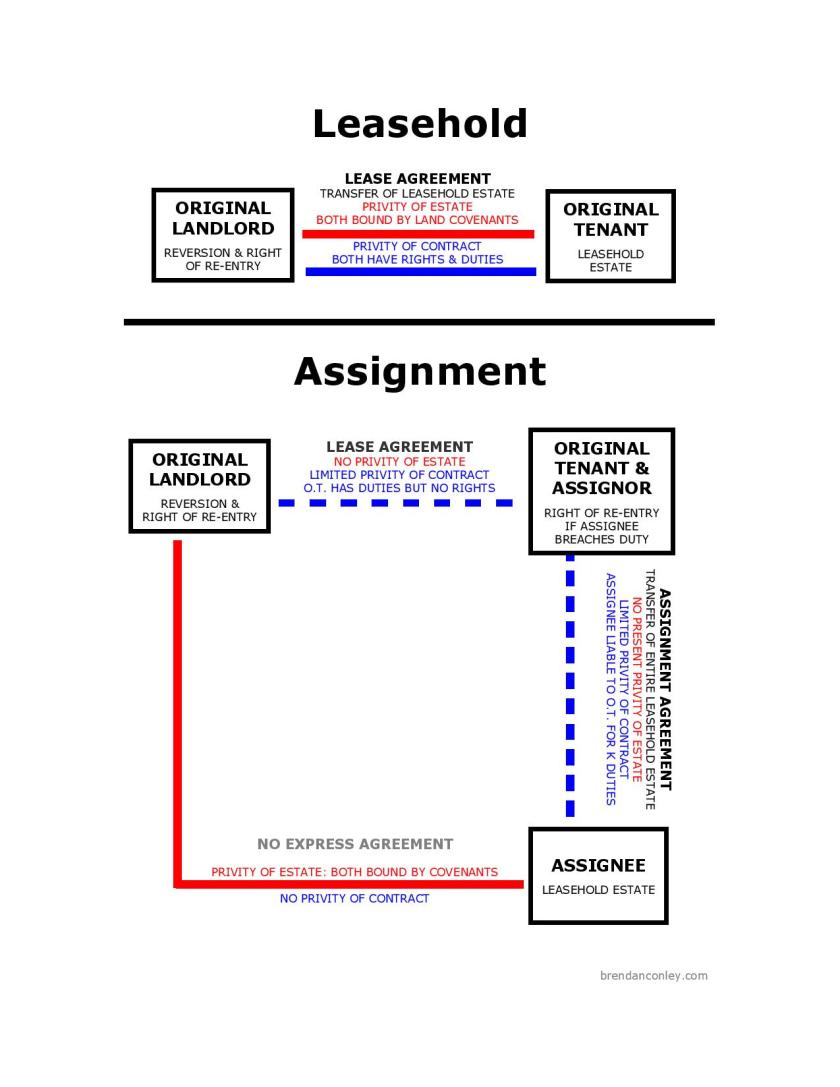

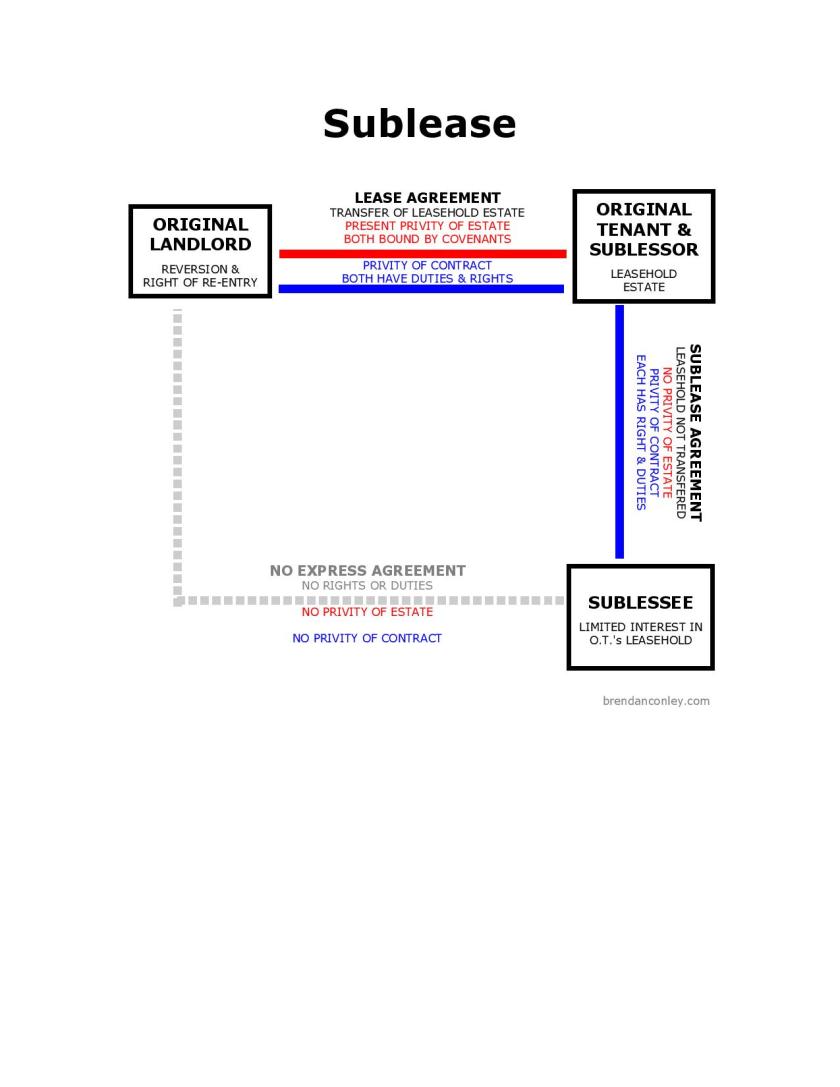

Access to the law is vital to the practice of law. Within the United States of America, we have numerous expansive databases with the law, some free and some with a cost. But how do we access international law? The thought of subscribing to dozens of individual country sites can be overwhelming. That’s where  The legal world abounds with rules and concepts that differ only slightly from one another, but that difference can make or break your legal case. One such instance is the difference between assigning and subletting a lease in real property. Essentially, both assigning and subleasing property result in the same end, i.e. someone new taking over the lease. The legal rights and responsibilities of the new lessee, however, differ greatly dependent upon assignment vs. sublet.

The legal world abounds with rules and concepts that differ only slightly from one another, but that difference can make or break your legal case. One such instance is the difference between assigning and subletting a lease in real property. Essentially, both assigning and subleasing property result in the same end, i.e. someone new taking over the lease. The legal rights and responsibilities of the new lessee, however, differ greatly dependent upon assignment vs. sublet.

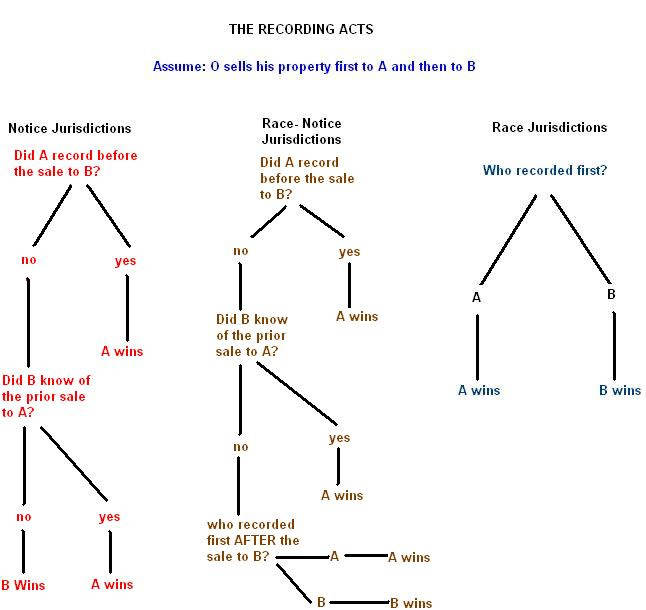

We all know how important individual words within a rule or statute can be when applied to a particular fact pattern. This is especially true when the rule is short, so you know that each and every word within it was chosen with care. An example is the

We all know how important individual words within a rule or statute can be when applied to a particular fact pattern. This is especially true when the rule is short, so you know that each and every word within it was chosen with care. An example is the