The legal world abounds with rules and concepts that differ only slightly from one another, but that difference can make or break your legal case. One such instance is the difference between assigning and subletting a lease in real property. Essentially, both assigning and subleasing property result in the same end, i.e. someone new taking over the lease. The legal rights and responsibilities of the new lessee, however, differ greatly dependent upon assignment vs. sublet.

The legal world abounds with rules and concepts that differ only slightly from one another, but that difference can make or break your legal case. One such instance is the difference between assigning and subletting a lease in real property. Essentially, both assigning and subleasing property result in the same end, i.e. someone new taking over the lease. The legal rights and responsibilities of the new lessee, however, differ greatly dependent upon assignment vs. sublet.

What is the legal definition?

assignment. The transfer of rights or property. Black’s Law Dictionary (2014)

sublease. A lease by a lessee to a third party, transferring the right to possession to some or all of the leased property for a term shorter than that of the lessee, who retains a right of reversion. Black’s Law Dictionary (2014)

When can a lessee transfer their rights in a lease? The Restatement of the Law 2d, Property states:

§15.1 Freedom of Transfer

The interests of the landlord and of the tenant in the leased property are freely transferable, unless:

(1) a tenancy at will is involved;

(2) the lease requires significant personal services from either party and a transfer of the party’s interest would substantially impair the other party’s chances of obtaining those services; or

(3) the parties to the lease validly agree otherwise.

What happens when those rights are transferred? The Restatement of the Law 2d, Property continues:

§16.1 Obligation Created by an Express Promise–Burden of Performance After Transfer

(1) A transferor of an interest in leased property, who immediately before the transfer is obligated to perform an express promise contained in the lease that touches and concerns the transferred interest, continues to be obligated after the transfer if:

(a) the obligation rests on privity of contract, and he is not relieved of the obligation by the person entitled to enforce it; or

(b) the obligation rests solely on privity of estate and the transfer does not terminate his privity of estate with the person entitled to enforce the obligation, and that person does not relieve him of the obligation.

(2) A transferee of an interest in leased property is obligated to perform an express promise contained in the lease if:

(a) the promise creates a burden that touches and concerns the transferred interest;

(b) the promisor and promisee intend that the burden is to run with the transferred interest;

(c) the transferee is not relieved of the obligation by the person entitled to enforce it; and

(d) the transfer brings the transferee into privity of estate with the person entitled to enforce the promise.

(3) The transferee will not be liable for any breach of the promise which occurred before the transfer to him.

(4) If the transferee promises to perform an express promise contained in the lease, the transferee’s liability rests on privity of contract and his liability after a subsequent transfer is governed by subsection (1)(a).

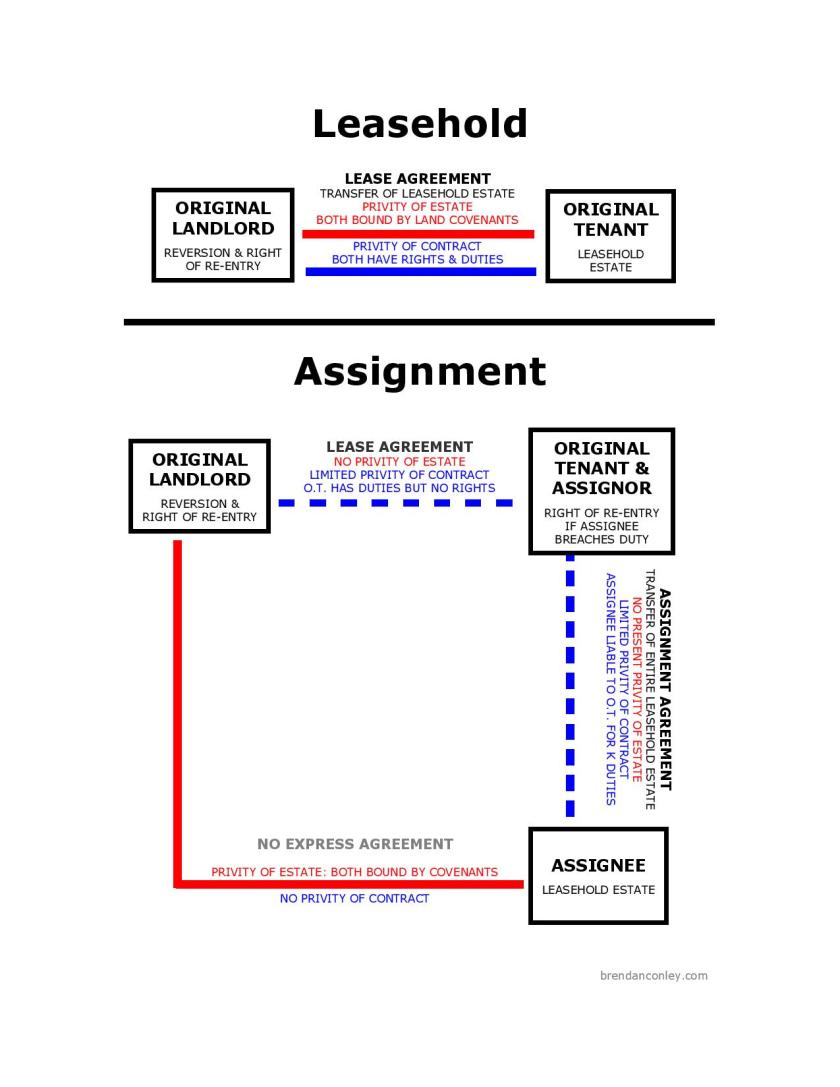

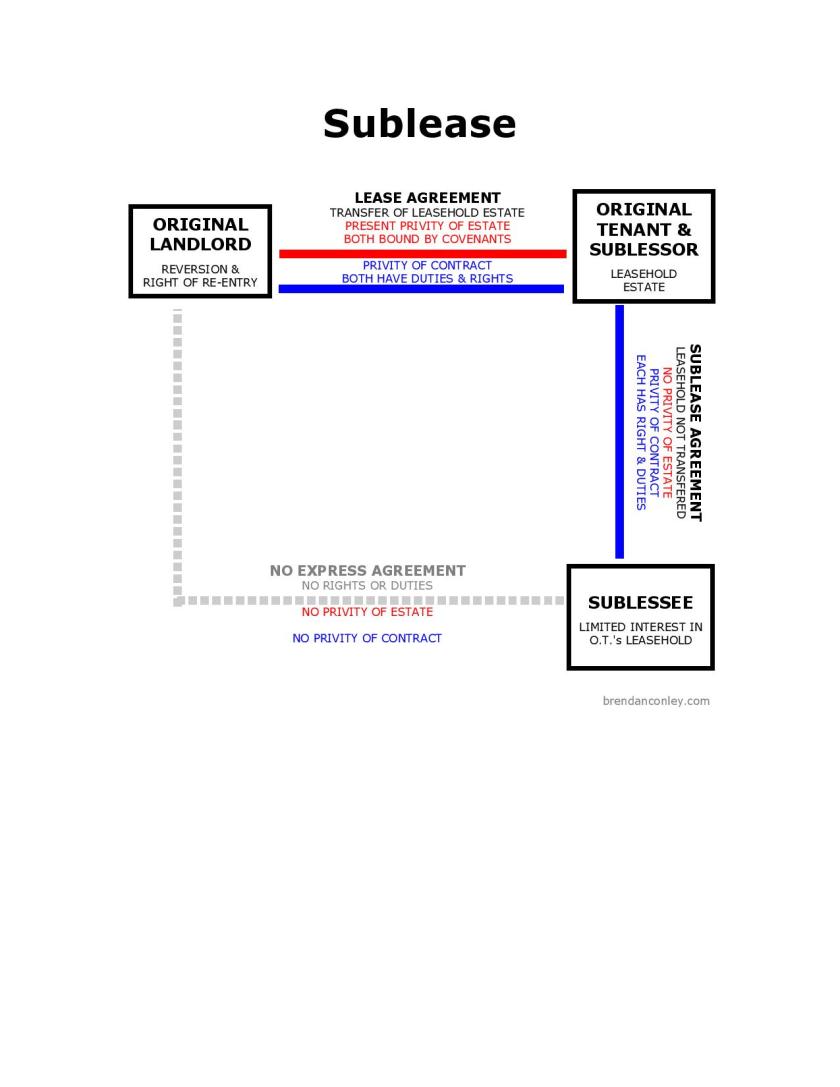

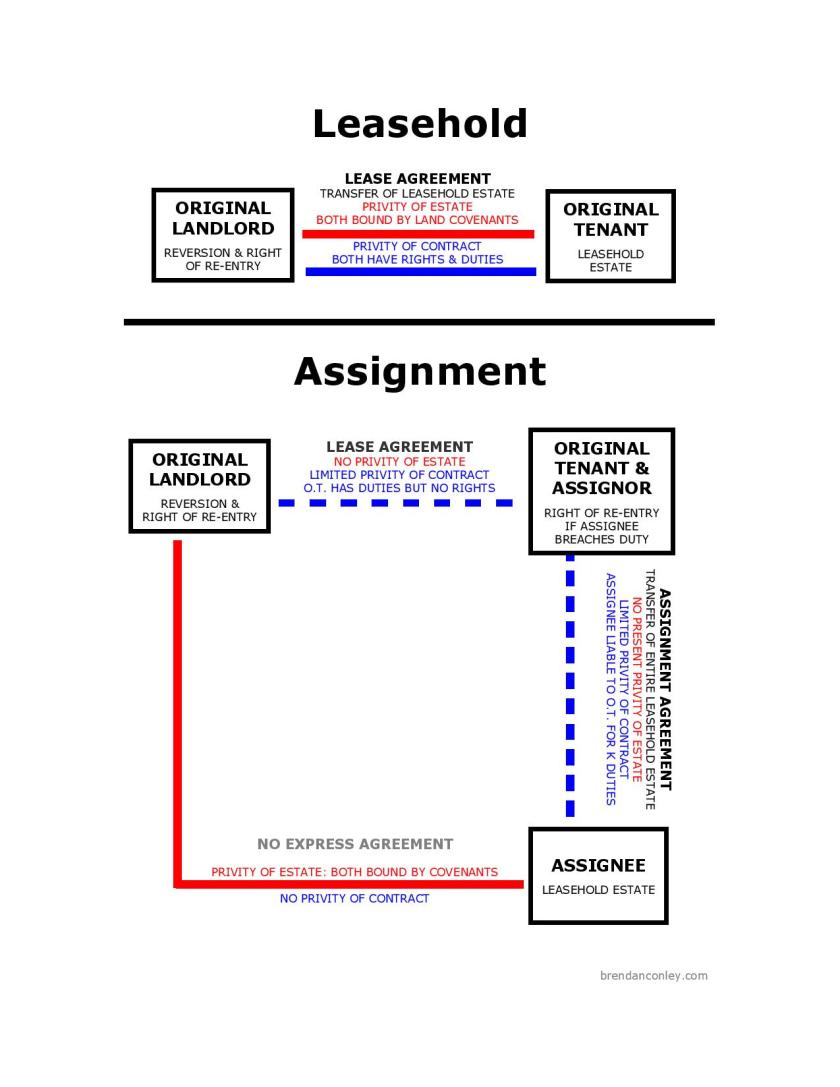

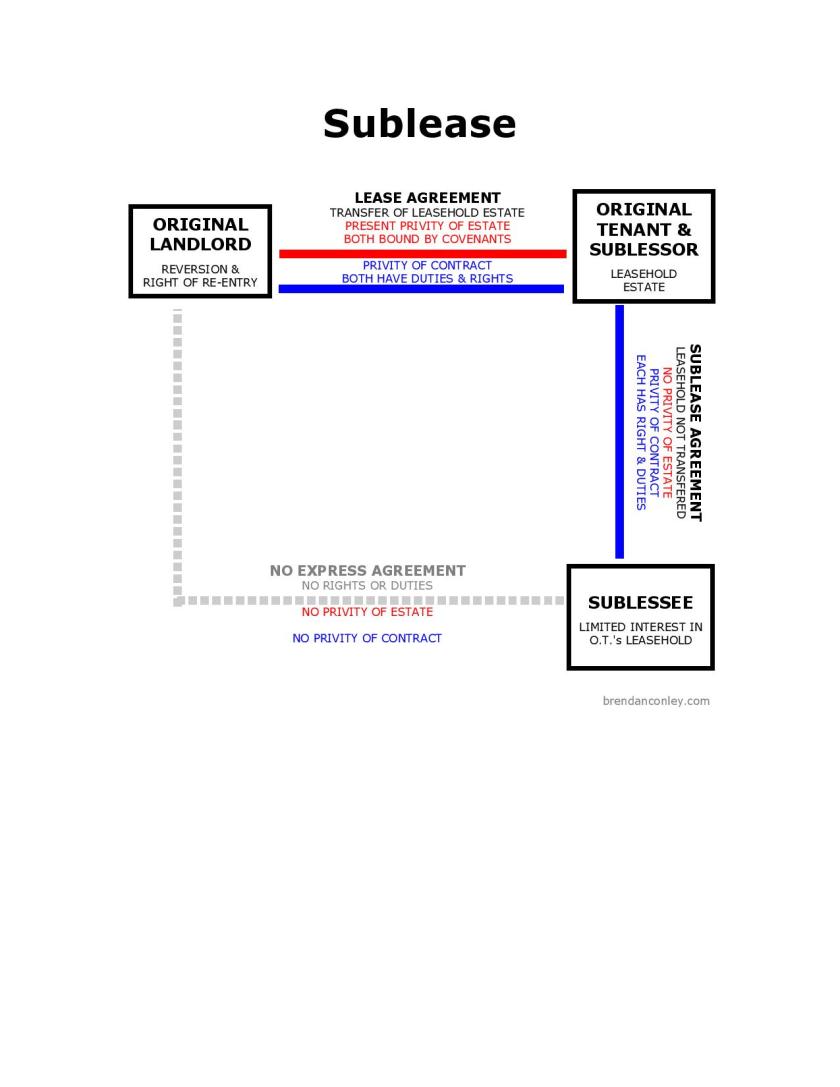

Crystal clear, correct? Essentially, a lessee may transfer their rights in a lease as long as it does not violate §15.1. This transfer may invest certain obligations in the transferee dependent upon what is transferred. If the original lessee transfers their rights via assignment, they are essentially transferring all of their rights for the remainder of the lease, thereby establishing privity of estate between the transferee and the original lessor. If the original lessee transfers their rights only partially, i.e. by subletting a portion of their lease (either rooms or a length of time), but retaining a portion of the lease for themselves, the transferee is NOT in privity of estate with the original lessor.

What does all this mean? An assignee is treated as the original tenant under the contract between the lessor and the original lessee. A sublessee is not; rather, a sublessee is essentially the tenant of the original lessee. If the original lessee fails to make rent payments to the lessor, the lessor cannot sue the sublessee for those payments.

The difference comes about based on whether privity of estate exists.

privity of estate. A mutual or successive relationship to the same right in property, as between grantor and grantee or landlord and tenant.

In an assignment scenario, the assignee is in privity of estate with the original landlord, thereby making the assignee responsible for certain obligations that fall within that privity. Contrarily, the sublessee does NOT have privity of estate with the original landlord. In a sublease scenario, the original landlord’s only recourse for violations of privity of estate are against the original lessee.

The landlord (original lessor) may still sue the original lessee, regardless of assignment or sublease, if any terms of the contract are violated because the landlord and the original lessee remain in privity of contract UNLESS the landlord releases the original lessee from such obligations.

privity of contract. The relationship between the parties to a contract, allowing them to sue each other but preventing a third party from doing so.

With privity of contract, both parties are obligated and both may sue each other if they fail to complete the terms of the contract. In a subletting scenario, the sublessee cannot sue the original lessor, nor can the original lessor sue the sublessee. Contrast this with the assignment scenario where, if the landlord agrees, essentially a new contract is created between the original lessor and the assignee, thereby creating privity of contract.

And for those visual learners out there, here’s a simple chart to help you remember who has privity with whom and when.

Black’s Law Dictionary defines a tort as:

Black’s Law Dictionary defines a tort as:

Negligence. That tort of all torts you studied in law school. So many types and so many applications. For the nitty-gritty, you should bunker down with your course notes, a good supplement, and the Restatement of Torts. But if you want a refresher on the general definition, you’re in the right place.

Negligence. That tort of all torts you studied in law school. So many types and so many applications. For the nitty-gritty, you should bunker down with your course notes, a good supplement, and the Restatement of Torts. But if you want a refresher on the general definition, you’re in the right place. The

The  “Procedural due process inquires into the way government acts and the enforcement mechanisms it uses. When government deprives a person of an already acquired life, liberty or property interest, the Due Process Clauses of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments require procedural fairness.” Constitutional Law in a Nutshell, pg. 274. Essentially, the government must use a procedural framework that “promotes fairness and transparency.” Acing Constitutional Law, pg. 125. Rather than using a narrow definition of these terms, the Supreme Court has interpreted “life, liberty, or property” quite broadly.

“Procedural due process inquires into the way government acts and the enforcement mechanisms it uses. When government deprives a person of an already acquired life, liberty or property interest, the Due Process Clauses of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments require procedural fairness.” Constitutional Law in a Nutshell, pg. 274. Essentially, the government must use a procedural framework that “promotes fairness and transparency.” Acing Constitutional Law, pg. 125. Rather than using a narrow definition of these terms, the Supreme Court has interpreted “life, liberty, or property” quite broadly. This does not mean, however, that you cannot advocate on your client’s behalf to introduce parol evidence to the court. You can, and should do so if applicable, so long as you can argue that the parties did NOT intend the contract at issue to be the final written agreement. Of course, you may be able to pursue alternative means of retribution for your client if the court rules that the contract is, in fact, intended to be the final written agreement between the parties.

This does not mean, however, that you cannot advocate on your client’s behalf to introduce parol evidence to the court. You can, and should do so if applicable, so long as you can argue that the parties did NOT intend the contract at issue to be the final written agreement. Of course, you may be able to pursue alternative means of retribution for your client if the court rules that the contract is, in fact, intended to be the final written agreement between the parties.

The legal world abounds with rules and concepts that differ only slightly from one another, but that difference can make or break your legal case. One such instance is the difference between assigning and subletting a lease in real property. Essentially, both assigning and subleasing property result in the same end, i.e. someone new taking over the lease. The legal rights and responsibilities of the new lessee, however, differ greatly dependent upon assignment vs. sublet.

The legal world abounds with rules and concepts that differ only slightly from one another, but that difference can make or break your legal case. One such instance is the difference between assigning and subletting a lease in real property. Essentially, both assigning and subleasing property result in the same end, i.e. someone new taking over the lease. The legal rights and responsibilities of the new lessee, however, differ greatly dependent upon assignment vs. sublet.